The Palimpsest

“Tradition is not the worship of ashes but the preservation of fire.”

— Gustav Mahler, unless it was Benjamin Franklin, or Jean Jaurés; possibly after a line of John Denham

“It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to.”

— Jean-Luc Godard

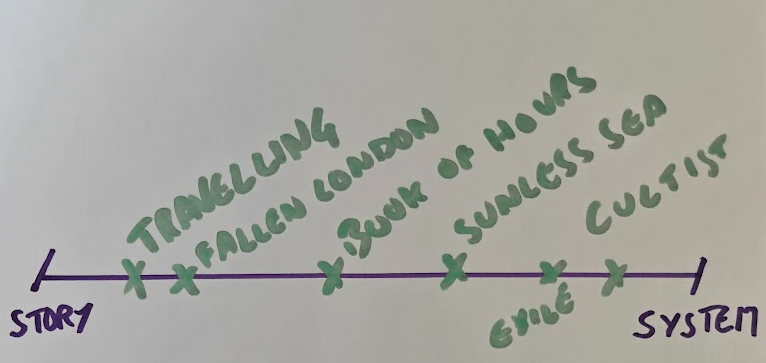

Fallen London and Sunless Sea and Cultist Simulator and Book of Hours: none of them fit in an existing genre (although Cultist spawned a microgenre of its own). All those other games had references and influences, but they all went in all the directions.

Consider my list of influences for Sea: ‘FTL; Don’t Starve; Strange Adventures in Infinite Space; Sid Meier’s Pirates; Taipan; Elite; roguelikes; the Crimson Permanent Assurance; the Irish immrama myths’.

Now look at our list of influences for Travelling at Night: ‘Disco Elysium, Planescape: Torment, Fallout 1+2’.

Two of the influences on Travelling’s list were developed by one studio; the same people worked on three of them; and Disco’s most avowed influence was Planescape. It’s not an exhaustive list, of course, but the other games that we might cite as influences (HBS’ Shadowrun games, or the OG BGs, or Obsidian’s work as the successor to Black Isle, or Owlcat’s neo-iso tradition) are all ultimately in that Interplay/Black Isle tradition. So Travelling has clear conventions, innovations, precedents that we can – in fact, we have to – acknowledge or follow or ignore.

Stop throat-clearing, Kennedy, we want to hear about Travelling! I’m going to talk about Travelling, but first I’m going to talk a bit about opera. Don’t worry, I know very little about opera, it won’t take long.

In fact the only time I ever regularly went to the opera was when I was living in Łódź in the mid-90s. I had almost no money, and the opera was well-subsidised in Poland back then, so the tickets were actually cheaper than the cinema. Polish surtitles for Italian language-opera weren’t really accessible to an English expat, but I could sit in the warm and feel cultured. A memory surfaces of an embarrassing conversation with a nice Scottish expat friend in the lobby of the Teatr Wielki in the winter of ’95. To appreciate the full effect of the experience, you need to imagine me as I was then, with beard and ponytail, in an embroidered waistcoat and bow tie, like an extra-hairy budget boho Frasier:

Jeff: So what have we come to see then?

1990s AK: [condescendingly] To hear, Jeff.

Jeff: Sorry?

1990s AK: [very condescendingly] You mean, what have we come to hear.

Jeff: Och sorry! What have we come to see here?

So opera. Unlike CRPGs, it emerged in Florence in the early seventeenth century. But like CRPGs, it’s a hybrid form that aspired to be a new kind of artistic expression with its own distinctive style. And like CRPGs, it developed its own distinct and distinctive traditions and conventions (we’ve talked about this before).

What kind of traditions and conventions? For instance, an opera is a fundamentally narrative form; operas have overtures; opera makes use of the distinctive bel canto vocal style which feels like listening to a nice Sauternes (yes still channeling Frasier. Deal with it)

Wait a minute, you say, I like a bit of Wagner, and he made a point of rejecting bel canto. He did! for a more dramatic, more heroic style which unsympathetic listeners might call ‘shoutier’ and I would call ‘more like listening to bourbon than Sauternes’. Fair enough, bel canto is really an Italian opera thing, clue is in the name.

Wait a minute, you say, Einstein on the Beach has no narrative to speak of, and it’s clearly an opera. Well Glass has his detractors, and though I like his work a great deal I don’t know if I’m brave enough to sit through five hours of it without an intermission, but yes of course it’s an opera unless you’re going to be needlessly mean. (And you’d have to be meaner even than Niles Crane: ‘His productions are brilliant. He staged a Philip Glass opera last year, and no one left.’)

Wait a minute, you say, Nixon in China has a prelude but it’s not an overture, it doesn’t preview the musical themes whatsoever, it’s just an atmospheric intro. True, I reply, although you seem suspiciously well-informed about opera, what are you doing reading a blog post about CRPGs – oh you know Nixon in China the same way I do, because you heard ‘The People Are The Heroes Now’ in the Civ 4 soundtrack…

Oay that’s enough opera. You take my point: there’s a consistent family resemblance even when people break with the conventions and traditions. More than that, you can get juice out of intentionally breaking the rules – as long as you know why you’re doing it. Conventions in art are Chesterton’s Fences. Sometimes you do need to knock ’em down, but you always need to think about ’em first

Back in ’95 – at the same time I was parading round a Polish opera house in my waistcoat – the Interplay designer Chris Taylor put together a vision statement for Fallout. (Huh, he designed Nemo’s War! I liked Nemo’s War.) Here are the bullet points from the original Fallout vision statement:

-

-

- Mega levels of violence.

- There is often no right solution. Like it or not, the player will not be able to make everyone live happily ever after.

- There will always be multiple solutions. No one style of play will be perfect.

- The players actions affect the world.

- There is a sense of urgency.

- It’s open ended.

- The player will have a goal.

- The player has control of his actions.

- Simple Interface.

- Speech will be lip-synched with the animation.

- A wide variety of weapons and actions.

- Detailed character creation rules.

- Just enough GURPS material to make the GURPSers happy. The game comes first.

- The Team is Motivated (‘Tim [Cain] has incriminating documents on all of us’, Taylor affectionately writes: apparently Cain was literally the sole developer on Fallout at the very beginning, but he managed to enthuse enough other Interplay employees to form an actual team)

-

(source)

If you look at all the later iso CRPGs (and indeed plenty of non-iso ones, like Bethesda’s Fallout sequels or the Silver Age BioWare games), then you’ll see they also follow through on a remarkable number of these aspirations. Some of the aspirations have fallen away – the ‘GURPS’ bullet point didn’t even make it into Fallout 1; most iso games don’t have facial animations even if they’re voiced; and in particular, as I’ve said elsewhere, Disco’s biggest innovation was to take the combat, point 1, entirely out of the CRPG formula. But it hangs together, doesn’t it?

You’ll notice that this list doesn’t include some of the features we expect in an iso CRPG, like…

a. dialogue trees

b. companions

c. a skill system

d. skills increase with use/experience

e. top-down/iso perspective with character sprites + character portraits

…because the features are ways to achieve the aspirations in the vision statement. This is a really fuzzy distinction – ‘a wide variety of weapons’ or ‘detailed character creation rules’ are features as much as aspirations – but I don’t want to get hung up on the taxonomy of it, that’s for the game studies PhDs, I just want to make the point that early on dialogue trees, skill systems, etc., became part of the CRPG tradition, even though it could have evolved totally differently. You could make an iso CRPG without them, just as you could put on an opera without a stage or a proscenium. But players would miss them. Even their limitations are part of the form.

Dialogue trees are a good example of what I mean. Like a lot of designers, I went through a phase of grumbling ‘we can do better than dialogue trees’. We probably can! At least in the sense that film and TV and video games are ‘better’ than opera and theatre, because you don’t need to dress up and go out and pay for tickets and all that stuff. But just as there’s something ceremonial and fun in dressing up and going out, and experiencing a unique performance, there’s benefits from even the limitations of dialogue trees.

For instance, we get tired of lawnmowing the tree (thinks: why did it never occur to me until now how weird it is to ‘mow’ a ‘tree’). You probably know the term: if you see a row of possible conversation topics, you know you probably either have to read all of them eventually, or miss out on something. If you’re enjoying the writing, this can feel like Christmas; if you’re not particularly enjoying the writing, it can feel like homework.

Sometimes designers try to work round this, for example by limiting engagement – e.g you only get to ask them two questions before they say ‘enough for now’. I put an experiment in Fallen London years ago where you were sitting in a box at the theatre with your interlocutor – you had limited questions, and every time you asked a question, you missed a bit of the play. This can be fun! But it can also worry or confuse players who are used to the familar rhythm of mowing the lawn, buzz buzz, smell of cut grass, where they feel like they’re being punished for behaving naturally when the conversation ends. Tradition and convention, again. And expectation.

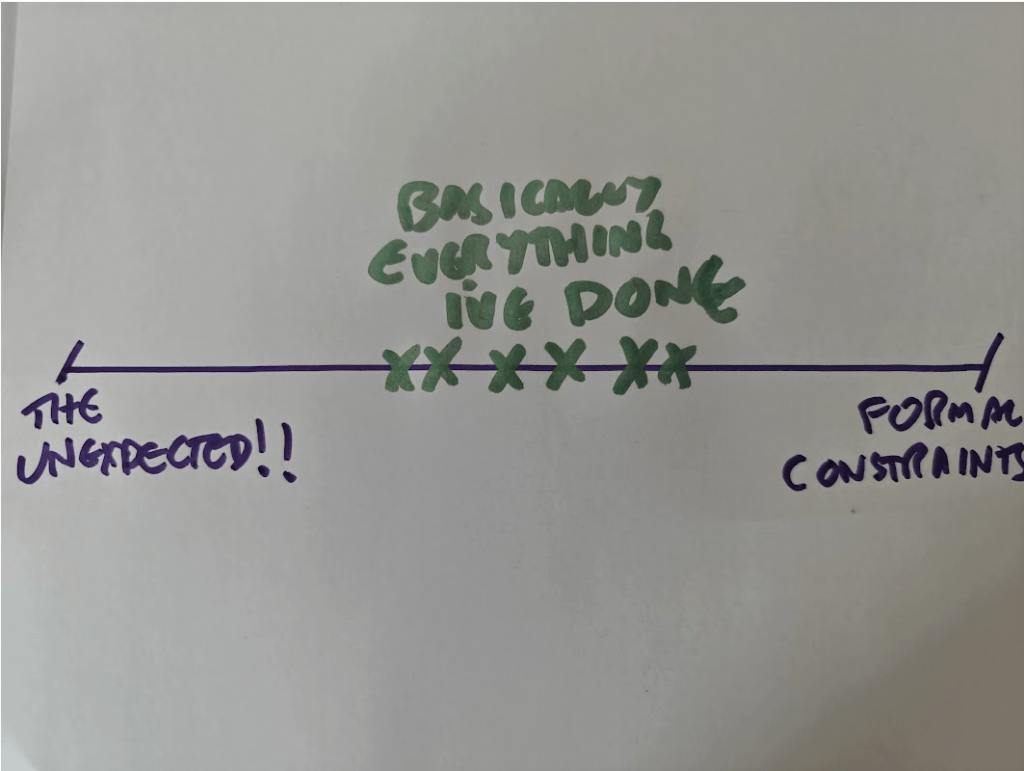

Let’s wrap this up. System and story: a good system is stuff that happens predictably and a good story is stuff that doesn’t happen predictably. I don’t mean that a good story needs to be a twist every scene, but if you know everything that will happen, it’s dull. Similarly a system will throw you surprises every so often, but it’s designed so that once you understand it, you can appreciate it and use it to predict the results of your actions.

Here are the games I mentioned at the beginning of the blog post, on a continuum from story-focused to system-focused:

I’ve spent happy years working near the right-hand end, in the poetic space where the systems support the story. Contentment only lasts sixty seconds in Cultist; Sunless uses its systems to make you think about hunger and the dark. Travelling is the farthest left I’ve ever gone. That made me disconsolate for a few weeks, because I really like working consonately with a structure… but then I realised something.

Right at the top I mentioned HBS’ Shadowrun games (Returns, Dragonfall, Hong Kong). I really enjoyed these – I was surprised how much, because a lot of the component parts are only ‘good’ or ‘very good’, but the whole works together fluently. I was also reminded by a chap on the Disco subreddit that the Shadowrun games pioneered a RHS dialogue interface, back in 2013 – although a very different one –

Part of the reason, I’ve realised, that I enjoyed Shadowrun so much is that the rhythm. You go on a heist of some sort; there’s generally a plot twist; you return to your hub; you talk to people and resupply; you go on another heist. It’s a formal constraint – a system – a foothold of predictability on the excitingly treacherous crag of narrative uncertainty.

This is a good intuition pump for one of the uses of ‘systems’ in narrative games – basically, they’re not just CYOA. A structure might be a skill system. A structure might be a reasonable expectation that the murderer in a whodunnit will not turn out to be ‘some bloke called Phil, who has never been mentioned at any point before now but you could find in a random monster encounter’. Either way, it allows the designer to set expectations, and the player and designer to benefit from a mutual understanding.

Fig. 4:

| How Interactive Narrative Worked In The Dawn Times | How it Got Better |

| Do you want to run through the fire or the ice? | Do you want to run through the fire or the ice? |

| 1. Fire–> It’s dying down actually. You win 2. Ice–> You slip and break your neck! lmao |

1. Fire–> If you’re wearing dragonleather underwear, you’re fine, otherwise you die 2. Ice–> The higher your Dexterity, the higher your chance of not dying |

Point being, game systems, act structures, conventions, are all different ways (not ‘just’ different ways! detail matters!) of providing these expectations. Which allows me to post Fig. 5, which I find reassuring:

Travelling at Night still exists in that nice structured poetic space. It’s just got even more words.

when you think of how many words your previous works had (complimentary), one can only pavlovianly drool at the sentence “it’s just got even more words”

thank you

ps: jfyi, i’m thinking the comment system isn’t back yet for mobile browsers?

Interesting, interesting stuff. Personally, I’m all for knocking down fences in art; I mean, the worst thing that can happen is that you make something no one will enjoy. (Well, actually I guess that could be a pretty bad outcome. Probably best to do it in the development/testing phase before you sink all that time and money in.)

Always glad to see Strange Adventures in Infinite Space mentioned, too! Always enjoyed that one.