It’s Not a Codex

There’s never been a ‘codex’ (or encyclopaedia, or lore compendium) in any game I’ve written. I hope there never will be. Mystery is the robe of the numinous! Imagine Twin Peaks if you paused to consult a codex every scene. Imagine Book of the New Sun with every enigmatic phrase immediately defined in parentheses. Imagine a sunset with hyperlinks. OK, that’s grandiloquent, but imagine Fallen London or Cultist Simulator if the first time you met the word ‘Vake’ or ‘Bazaar’ or ‘Long’ or ‘Meniscate’ you could just read a codex entry explaining exactly what it is.

I’ll phrase that last bit more precisely, because you sort of can, actually, if you alt-tab out. There is a fan wiki for every game I’ve ever written. You can look up any of the words I mentioned above and radically spoil the intended experience of slowly marinating in the way the meaning develops over experience.. I can’t do anything about that – I probably shouldn’t even want to do anything about that, because people like different things. It’s a done deal. So to phrase it more precisely: imagine if I had written these games in the expectation you would have to use those codex entries. It means that without the codex, the experience would be incoherent, and it requires use of the codex. It becomes like reading a novel in a foreign language you barely speak, and being forced to long-press on the screen every tenth word to understand what’s going on. It is no longer about building an experience where the discovery sine-wave – mystery, confusion, aha! – requires thought and artistry on the writer’s part. That thought and artistry is either never applied, or it’s undermined.

Let me give a couple of examples of that undermining. These examples are from well-made, intelligent games which I enjoyed, and I’m not attacking them! They’re just, also, from games which took an established mainstream approach, and I want to talk about why we’re not taking that approach.

First example below. In Deadfire, Obsidian put considerable effort into their pseudo-Italian, in the expectation that people could piece together meaning from context and general Romance language etymology… and then the UI obligingly taps you on the shoulder and tells you the answer. Like giving someone a crossword already filled in. Meanwhile, Berath is the god who gave us our main quest in the first scene of the game. If a player makes it this far in and needs to be reminded who he is, they’re a lost cause. The rest of us feel intermittently patronised every time we see his name highlighted.

One reason is that a studio wants to address as wide an audience as possible, including people who are absent-mindedly playing the game while second-screening Sons of Anarchy, and they don’t have the indie luxury of appealing to an attuned and attentive audience. We, however, do.

A second reason is that a studio has considerable number of writers working on disparate parts of a game over years, and it’s harder to plan out a Dune-like osmotic context seep when people can do a hundred sub-quests in a thousand different orders. (You know Herbert spent five years rewriting and revising Dune? Those epigraphic chapter headings represent a lot of architectural work.) We, however, have exactly one writer.

And a third reason, relevant here, is that sometimes there really is an urgent practical need to introduce a complex background so people can appreciate the story. I think in an ideal sense, this is just never true. If the context needs explaining, focus on the bits that don’t need explaining and let people miss what they don’t need. It’s not a documentary!

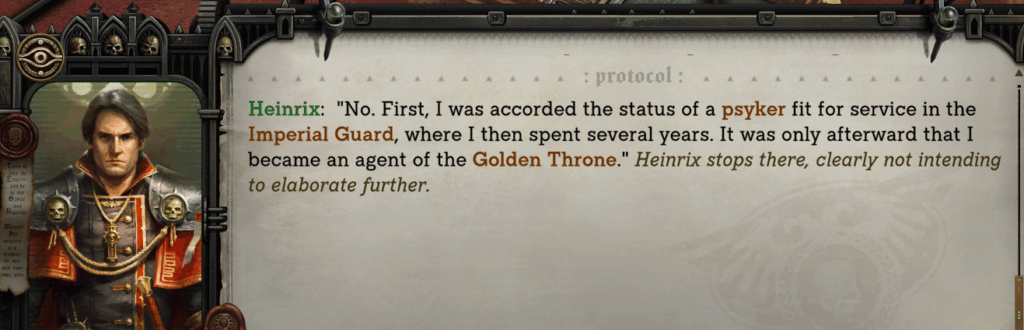

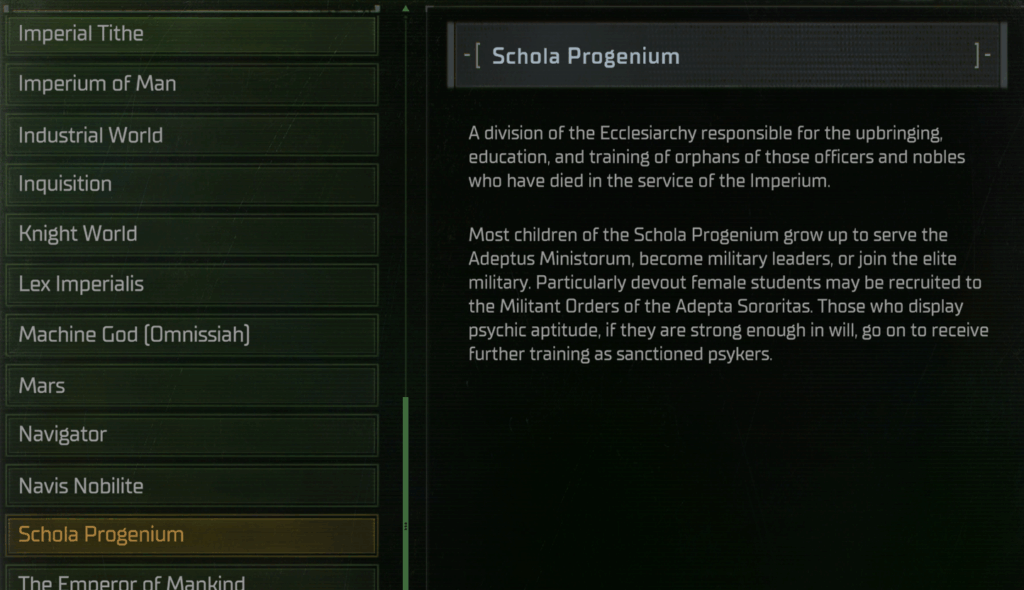

But – example 2 below – if you’re making Owlcat’s (excellent) Rogue Trader – a licensed game in a forty-plus-year-old setting – and you need to appeal to both newcomers and veterans, you can’t just decide to cut out the less relevant background. And you really do need the tooltips.

So here, at worst. it’s a necessary evil. But it needs a codex behind it. And for many of us, seeing a codex entry like this sinks our souls in marshy fear. Have you done enough homework? Are you going to be ready to answer questions later?

—

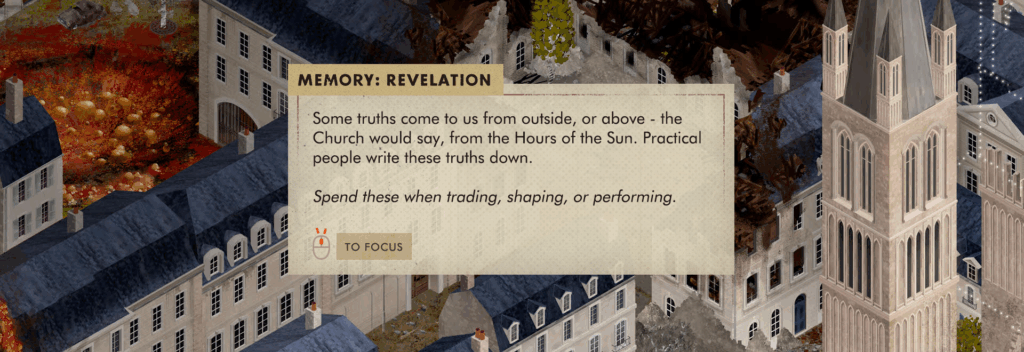

Travelling at Night is not a licensed game nor a forty-year-old setting. But it is an eight-year-old setting which has served two notoriously obscure games, where we need to cater to newcomers who won’t know what the hell an Hour is alongside Cultist veterans with nuanced opinions on the difference between Aspects and Principles.

So I’ve caved to the inevitable and we’ve added a feature to help orient the confused. But it’s not a codex. It’s not.

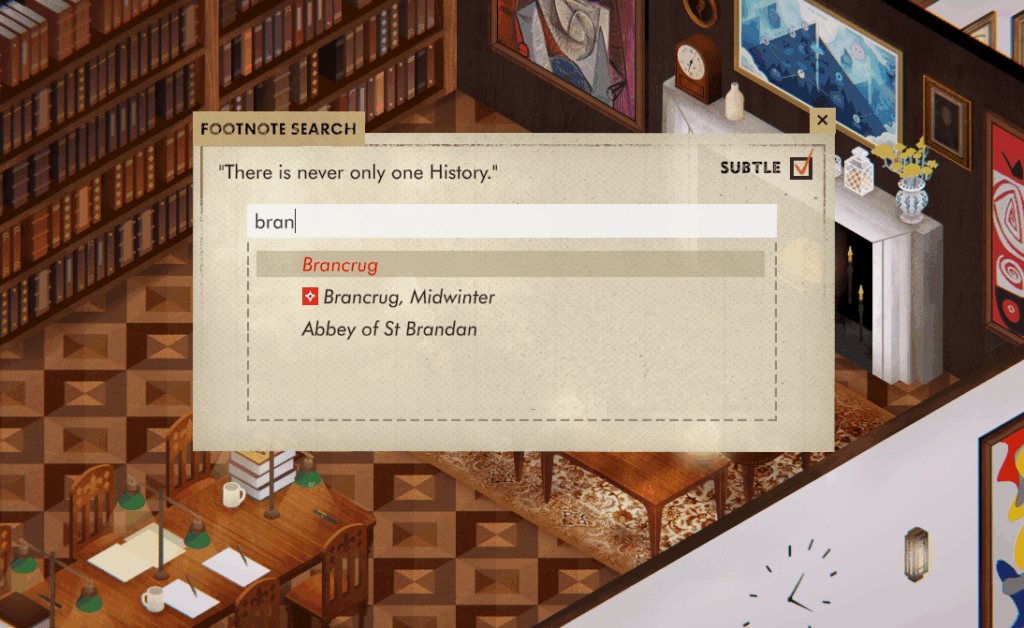

Okay, it’s got some codex-like features. You can search for a topic, for instance:

What’s that star-marker? Is it an ‘unread’ marker? No, because the search feature only shows things you’ve already seen. We want to retain as much as we can of that drip-feed artistry, and we don’t want to inspire that looming fear of homework. We’ll come back to the star-marker in a minute. It’s one of the (relatively few) ways in which our Footnotes differ mechanically from a traditional codex. The main difference is one of approach.

I can think of at least one wildly famous example of a narrative which prominently featured something you might call a codex. In fact it didn’t just feature it prominently; it was a central character.

Any ideas?

Click the blurred image below to see what I’m thinking about.

That’s the 1981 TV show version of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which featured animated segments where the Guide itself glossed or riffed on or foreshadowed the narrative. Do take a minute to watch the animated bit of that video. It glosses and foreshadows the point I’m about to make. It’s also very funny.

My point is this. A game shows, a codex tells. Does that Hitchhikers segment show or tell? The only meaningful answer is ‘yes, definitely’. You can see something similar in Susanna Clarke’s pseudo-scholarly footnotes in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, or, to take it a step further, the metaleptic1 commentary and index in Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

So Travelling at Night is going to feature animated codex elements? Or I’m going to write like Adams, or Clarke, or Nabokov? Thankfully we don’t need to do any of that. We just need to find ways to make the transition between text and footnotes2 mildly entertaining, or otherwise make sure the two elements work together as parts of a whole intented experience.

I’ve just demonstrated a really, really simple way of doing that in the images above! You’ll notice all of them have captions, which make an observation or mention something semi-relevant. They’d be meaningless without the actual images.

Similarly, this is not really useful out of context, but the original link provides the context, and the concision means it doesn’t overstay its welcome.

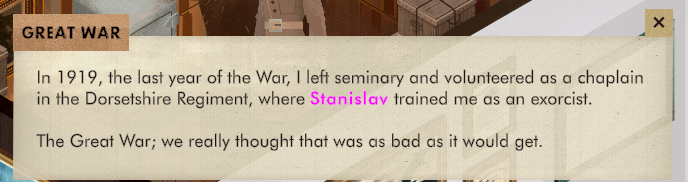

Or we can move away from the encyclopaedia tone of a codex entry into the first person, alongside some emotionally establishing commentary.

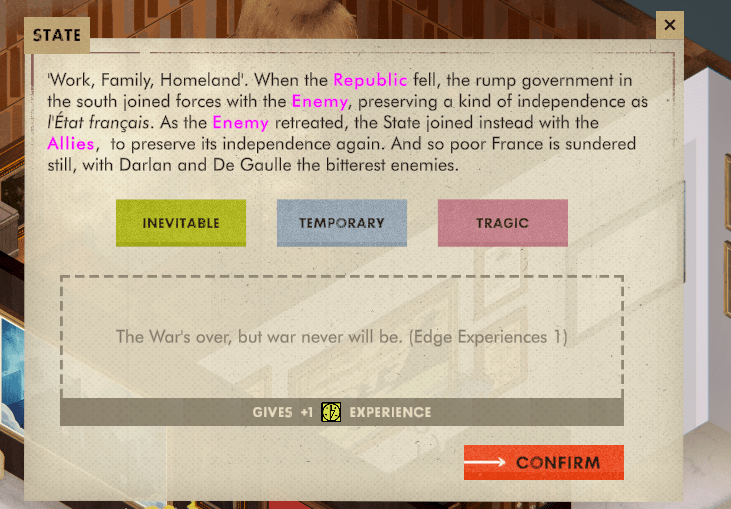

Sometimes it is really hard to avoid that encyclopaedia tone. I’ve rewritten this one a couple of times and will probably rewrite again because it’s still a little too expository, but there’s some basic information I want to make sure people don’t miss. Alt-history can be confusing. So we give people a small reason to care, and bend the flow back into the actual game experience:

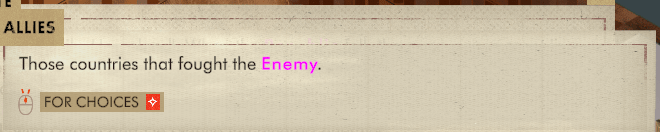

That star-marker I’ve mentioned above is a signal that there’s a snacky on the other side of the link. (You don’t remember to take the choice right away – we don’t have ‘unread’ markers, but we do track ‘unrealised choices’ so you don’t lose them.)

And once we’ve established that mechanism, we can use it to foreshadow more significant in-game choices.

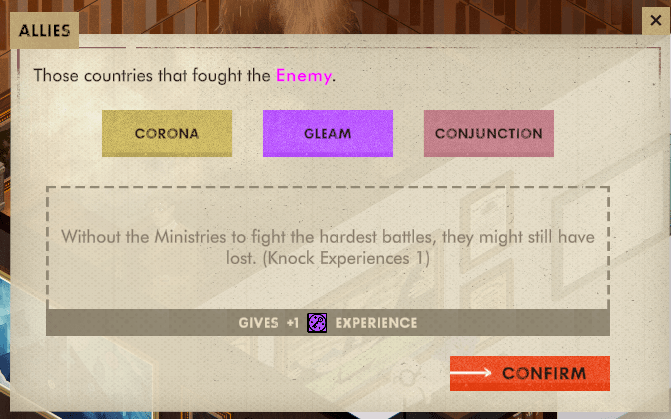

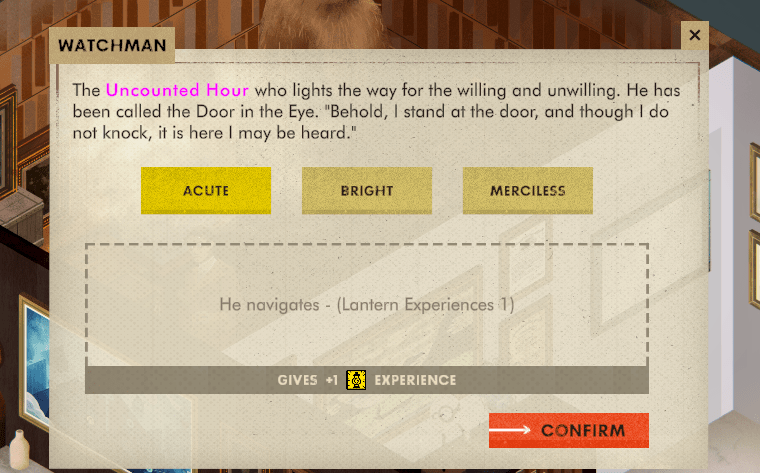

Or we can work with the player’s evolving understanding. ‘Tell me the Watchman is a Lantern Hour without telling me he’s a Lantern Hour.’

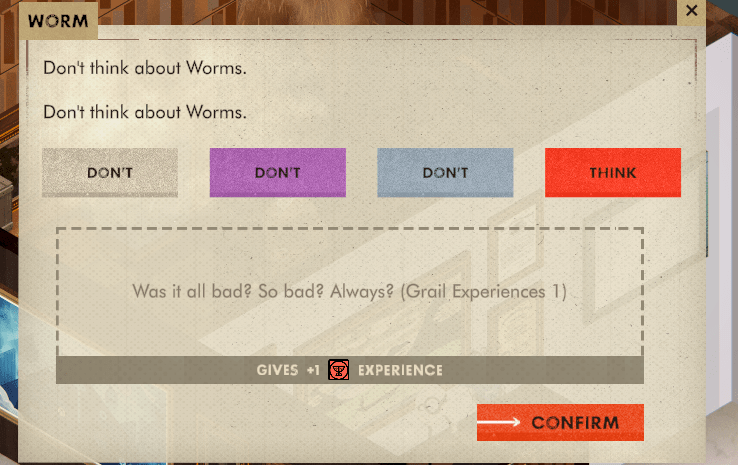

…or we can sidestep some basic expectations and engage emotionally and aesthetically as well as metatextually.

Was it all so bad? Always?

1 A nicely semi-obscure word useful for impressing people when you want to talk about ‘moving between different levels of narrative reality, like in a Stoppard play or an Ice Pick Lodge game’

2 ‘Transition between primary and secondary levels of narrative reality’: METALEPSIS, cool word

3 There’s no way to reach this footnote from the main text of this blog post. You’ve just read it because you finished the blog post or looked down after reading a real footnote. But I’ll mention in passing that the vibrant magenta link text is a placeholder colour – I just forgot to add the matching colours when I was styling the new version of the UI.

![Dialogue: 'And I doubt [Berath] and the opthe gods will consider your 'debt' to them fulfilled. [Merla], all of it.'Tooltip for 'Merla': 'a Vaillian expletive or curse.'](https://weatherfactory.biz/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/pallegina-1024x240.png)

![Caed NuaCaed Nua was a Dyrwoodan castle built over the ruins of the Endless Paths of [Od Nua]. Considered cursed, few ventured into its halls and even fewer made any effort to hold the castle or the lands around it. You became the de facto lord of the castle after defeating its previous master, the [Watcher] called [Maerwald]. As the [Watcher] of [Caed Nua], you ruled the stronghold until it was destroyed by [Eothas]. The god awoke from his slumber, occupied the adra beneath the castle and pulled himself out of the ground, destroying it in the process. See also: []Od Nua], [Maros Nua], [Eothas]](https://weatherfactory.biz/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/odnua-1024x362.png)

On the topic of codexes which only fill in as you progress through the game in order to represent the sum of what the player character(s) have beheld, one I would bring up is 13 Sentinels (Aegis Rim), and to a lesser extent its ancestor Odin Sphere.

13 Sentinels is a mad creation that cost Vanillaware’s employees several years of life and which states at the outset that it wants to tell the story with 13 point of view characters. And because that would be too simple, each individual story-line progresses in “Competition” with the others: they do not take place successively but simultaneously, to an extent. Sometimes the game will lock out one until you’ve progressed others so that they would make sense, or to make sure you’d be on the same page before its reveals occur, but the game tries to let you pick whoever you want, whenever you want, and collate the whole as you go along.

In this endeavor, the developers included two helpful things to support you: One, a codex which gradually fills over time, and Two, a timeline view which, again, pieces together which scenes occurred when so that, when it gets even more confusing, you can take a step back and ask “So where were we?”

I called Odin Sphere its ancestor because it did so to a lesser extent, with its five protagonists. They each have their respective stories, but you can only play them in sequence. Nevertheless, the game provides a scene navigation where their chapters run in parallel with color coding, again to clarify what happened when once you mix them all up.

Could someone please update the wiki to tell me which of the choices in the last 5 screenshots (less one) are the correct ones?

You’re goin’ on my list, Chalk

We’re too busy getting through your 400+ book of hours episodes, but get back to us in 30 years friend

That was an interesting lesson in game design. It definitely made me think about how I approach codices as a player.

I believe that, for me, part of the fun of both “Cultist Simulator” and “BOOK OF HOURS” was that I ended up making my own codex of a sort over time to understand what was happening. And while my solution only involved pen and paper, a friend of mine made a huge relational database in Notion to keep track of the inner workings of Hush House.

As you pointed out, diving into a wiki may spoil the experience. But both “Cultist” and “BoH” are games that are fun to write a wiki about.

On an unrelated note, how devious of you to tease us that codex entry about the Uncounted Hours.

One thing I’ve seen in a couple of games that I think works really well for indies is to have a place to take notes in-game. Maybe there’s set sections like ‘lantern’ but in that section players can write their own thoughts about what that might mean.

I’ve used steam’s notes app for the rest of the series, but an in-game notes function would be neat with like being able to pull up specific notes when hovering over something

You’re so awesome! I don’t believe I have read a single thing like that before. So great to find someone with some original thoughts on this topic. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This website is something that is needed on the internet, someone with a little originality!

Very interesting stuff. I grew up on the 1981 Hitchhiker’s Guide TV series! Anyway, I didn’t even realize there were so many issues to think about with such codices. Funny, I remember that Planescape Torment didn’t have any codices, did it? Well, it had lots of characters you can talk to, and then notes you made about stuff you learned. And somehow this conveyed enough information about Planes, the Lady of Pain and the Blood War. Good stuff.

Also, I greatly enjoy the metatextual shenanigans like “Don’t think about Worms”.

Also also, I feel like “shitwizard” is something people might yell at their opponents in an online shooter.