‘Embed the ending in the middle, or crush it up and stir it into the rest of the game.’

My Eurogamer column about endings: specifically, but not exclusively, the problems on endings in Fallen London.

If you like it, take a look at my previous columns. They’ve included pieces on gravity in games, an alternative history without D&D, the People’s Crusade as it relates to Kickstarter, and six reviews of nonexistent games.

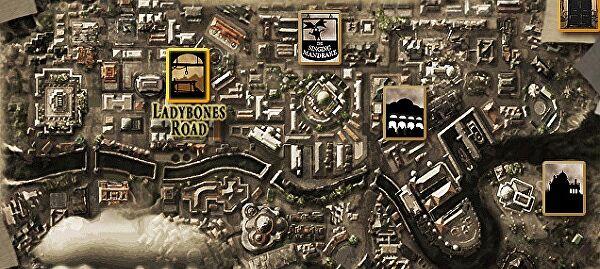

Fallen London’s an oddity. More than a million and a half words of sort-of-multiplayer online interactive fiction, free-to-play but polite about it, kinda grindy but absolutely crammed with story: a videogame with no moving pictures at all.* I originally built it, and I founded Failbetter Games, who still run FL. Yesterday I left Failbetter, so I can finally use Fallen London to illustrate a point without feeling like I’m plugging it. I don’t want to talk about Fallen London, exactly: I want to talk about endings.

For years (FL has been running for seven) people asked: how the hell is it going to end? It’s a story-based game, and one of the defining qualities of stories is that they have an end as well as a beginning and a middle. There are exceptions, but one of the defining qualities of a horse is that there’s a leg at each corner, even though some horses have three legs. Stories, basically, end.

How do you do that with a free-to-play game where players want to keep going forever? If a player can still play, their story isn’t over; if they can’t still play, they’re upset (and, candidly, they won’t make a free-to-play game any more money). This is a problem that (eg) MMOs face, too, but the story in MMOs is generally an afterthought. Fallen London, notoriously, has almost no gameplay. It’s all story.

We did settle on a solution – in fact, a couple. I’ll talk about that in a moment, but I want to say a few things about endings generally first.

One of my favourite, and Frenchest, quotes is something Balzac said: that coming up with ideas for stories is the fun bit like ‘smoking enchanted cigarettes’. Beginnings are fun; they’re barely more than an idea, and a promise of an ending. It’s much easier to make a promise than it is to fulfil it. To finish a story you need an ending, and endings are hard. (Middles are even harder, sometimes, but that’s another column.) There are a bunch of reasons for this – fulfilling that initial promise, being both surprising and inevitable, all that good stuff – but also, just finishing something, deciding when to call it done, is something that only seems easy to everyone who’s never tried to do it.

Deciding when to call a story done is even harder when player action can alter what happens. What if they do something that takes the plot elsewhere? The first-pass response to this, the one people usually expect, is to add multiple branching endings. The first problem with that is: when the hell do you know when to stop? You’ve just gone from a flat to a three-dimensional problem, and every writer of non-linear narrative knows the devouring temptation of adding just one more ending.

But in any case, multiple endings generally aren’t multiple endings, exactly, if the player keeps going after the first ending to look at the others. The first (second, third…) endings become late middle, epilogues to the real ending. Or, sometimes, the first ending is the Real Ending, the one that you chose in your personal headcanon. So even multiple-ending games still have one ending, and then one kind of epilogue or another.

Some games lock this down hard. Big CRPGs branch their endings based on stuff that happens earlier, so you have to replay the whole game to see something different – and that feels more like a reboot or a retelling, an extension of the same story. No one sane will reload a game from five hours back to view an alternate ending (although there are plenty of non-sane YouTubers to whom I am very grateful for their ending videos).

So if you have a big, long, slow feedback loop, you can make multiple endings feel like different endings. But that still doesn’t help with a game that can’t afford an ending at all. So Fallen London took two distinct approaches, with two different strategies: one, make sense of the desire to choose have an ending, but allow them continuity. Two, make players want an ending anyway.

Some games lock this down hard. Big CRPGs branch their endings based on stuff that happens earlier, so you have to replay the whole game to see something different – and that feels more like a reboot or a retelling, an extension of the same story. No one sane will reload a game from five hours back to view an alternate ending (although there are plenty of non-sane YouTubers to whom I am very grateful for their ending videos).

So if you have a big, long, slow feedback loop, you can make multiple endings feel like different endings. But that still doesn’t help with a game that can’t afford an ending at all. So Fallen London took two distinct approaches, with two different strategies: one, make sense of the desire to choose have an ending, but allow them continuity. Two, make players want an ending anyway.

The first approach was Destinies: what some people have called an ‘equippable ending’. At rare times of the year, characters can experience a dream of the future. They get to choose a really cool but also horrible thing that will happen to them as the first scene of the last act of their life. They bring back the memory of that dream, and equip it as a trophy item that gives stat buffs. They can change the dream later – exploring multiple endings – but in the meantime, they get to continue in the knowledge of the ending, seeing it have a real effect. “If you can’t solve the problem of players wanting closure or continuity, give them both.”

And the second approach was FL’s most demanding, aggressive, ridiculous storyline: the Search for Mr Eaten’s Name. Players are told that this quest will not end well, and that they’ll destroy themselves and everything they love (especially and mostly, their cool tools and phat lewts, but also their friends, spouses, past, future and more). If you know anything about human nature, you’ll have guessed that this is a tremendous hit with a minority of really core players – because of, not despite, the fact they’re working hard over a long period of time to set fire to their character and watch it burn. It’s not a con or a trick. There’s a huge amount of story in the Search. But the Search isn’t joking around when it gives the player a quality called A Bad End. “If you can’t solve the problem of players wanting closure or continuity, make them want closure.”

Non-linear stories work like and unlike linear stories. We’re still learning the unlike things that make them work. Even endings can be unlike. Sometimes, with a non-linear experience, you need to embed the ending in the middle, or, as it were, crush it up and stir it into the rest of the game. It’s even harder to decide when you’re done, but if you can’t decide when you’re done, you don’t have a story, just a mess of offcuts. And not all stories are tidy, even linear ones. Sometimes you just have to stop, right in the middle of everything.

* I was at the ceremony when Fallen London won Best Browser Game in 2009. The games in other categories were things like Warcraft and Arkham Asylum, so the looping ceremony video cut from high-end fight scenes to a camera panning optimistically across a beige web page. I couldn’t look anyone in the eye.