Building the Frontier

10.10.15

I didn’t talk about my own time in LambdaMoo, because that wasn’t really the point, but since you ask, I built a house in a very large mostly-dead dragon.

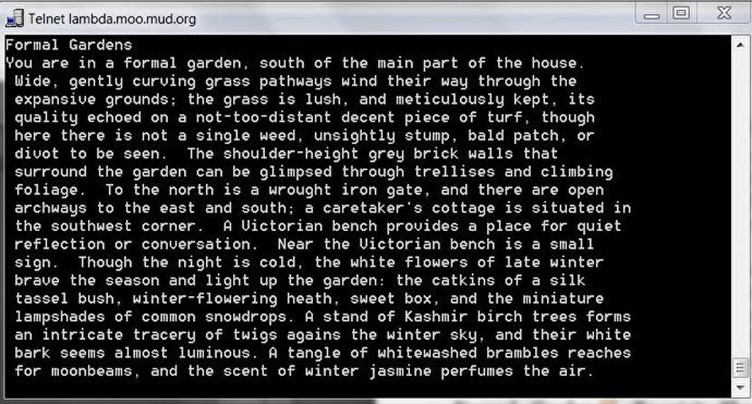

There was once a virtual world called LambdaMOO. It began when a researcher named Pavel Curtis recreated his Californian house inside a virtual space in a Californian computer, but the space was open to other players connecting from around the world. You could connect with a named avatar, chat, walk around and punch things by typing text commands –

Back up. It doesn’t sound impressive now, but it happened in 1990. This was the year of the first Wing Commander game, of the first Secret of Monkey Island. It was the year that a computer scientist in Geneva was writing the first web browser, and the year before the first website. The ZX Spectrum and the BBC Micro were still on sale. It was before Internet Explorer, before home Internet access, five years before the first graphical MMO. You connected to LambdaMOO via Telnet and a green screen terminal.

It wasn’t the first text-based virtual world. There’d been a number of text-based MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons) in the 80s. These were LambdaMOO’s immediate ancestors – the MOO stood for MUD, Object Oriented’. Curtis was working for PARC, a division of Xerox which did advanced, experimental, unexpected things. (PARC invented an alarming number of things, including fripperies like the laser printer and the mouse.) LambdaMOO was an attempt to see if something serious could be built out of online social environments like MUDs. Which were obviously trivial things of limited interest, back then.

Anyway, LambdaMOO was the first shared world which could be modified and extended by its users through the MOO programming language. So this was the frontier. And like most frontiers, it was both wide open and pretty rough. It was an all-text experience with a complex syntax, prone to unpredictable and devastating lag. But you could extend it: modify your character, add verbs, use the @dig command to create new rooms leading off existing ones –

Back up again. This isn’t about nostalgia. I want to point out that the first thing Curtis did when he created a virtual world was to add geography – in other words, make it non-trivial to get around. The house was a good-sized place with a complex internal layout. There was a street, there were gardens, there were sewers full of goblins underneath the house. You could easily get lost in that alone.

But behind the living-room mirror you could find the Looking-Glass Tavern, where new players generally attached the entrances to their homes. Those homes were where the geography got really complicated. The further you went from the mundane core of the house, the stranger and more delightful everything became, and the more complicated the the geography was. LambdaMOO had its share of haunting and delightful and inventive places, and all the players who added them wanted to make them effortful to get to. The LM Architectural Review Board had its hands full dealing with applications from people wanting to go beyond their location quota.

So it took real effort to find your way to the interesting places – but it took real effort from the builders to make it require real effort. Distance doesn’t exist in a virtual world unless you put it there on purpose. Remember, this was a world designed as a social environment. The whole point was to put people in the same room and let them talk to each other. But unless there’s distance, no one will take it seriously as a world. Unless there’s distance, you can’t explore: you can only browse.

Of course, once you’ve explored the world, distance goes from device to inconvenience. Originally LambdaMOO players had (I’m told) to create rings of teleportation, and use them to travel around. By the time I got there, the @teleport command was built in. Curtis went to all that effort to make the world hard to traverse, and one of the first things the inhabitants did was to abolish distance. Because distance is also a pain in the arse.

This is our old friend the Skyrim Problem. The first time you climb the Throat of the World, it’s an experience. It takes so long and you rise so far that there’s a real sense of achieving the sky. And once you reach the summit, when you look down at the road from Whiterun, it means something because you travelled that road. (Meeting the frost troll and having to backpedal and kite it to death with fire spells and keep reloading until that works spoils the mood, but that’s my fault for rolling a mage.)

I’ll remember that moment (the summit, not the frost troll) long after I’ve forgotten the dragon fights. But you need to go back and forth a dozen times from the monastery at the top of the mountain, and of course you’re usually going to use fast-travel. You’re going to use fast-travel to get from one end of Skyrim to another, to tick quests off, to get loot home in a hurry. You’ll stop experiencing the main point of Skyrim – all that stunningly realised distance.

And, you know, that’s actually okay. We often curate our experiences. The credit sequence of True Detective is stunning, but you might want to fast-forward when you see it for the tenth time. You don’t always listen to an album from beginning to end. You don’t have to eat all your vegetables every meal.

It’s funny when you think about it, though. Bethesda went to all that effort to put all the distance in the game. Then they went to more effort to let players take the distance out with fast-travel, under certain circumstances. And then – then – a minority of players built and used mods that blocked fast-travel. In other words, they went to more effort to put the distance back in again. (Conversely, we’re expecting to see a fast-travel Sunless Sea mod any day now.)

And, you know, that’s okay, too. But it’s not a solution, just a difference of approach for a few hardcore players. It’s not practical for many players to spend that amount of time walking around a map. When we complain about fast-travel, what we actually mean is, we wish we could relive the first part of a game – that sweet unfolding of possibilities – over again. We resent fast-travel because we think it’s robbed us of that experience, but usually that experience is already past.

The fact it’s past doesn’t mean it’s gone, though. Once you’ve experienced the geography, it’s in you. It’s part of your story. If the experience is a good one, you’ll regret its passing, and you’ll yearn to revisit it – but that’s the nature of the past. It can only be grasped in moments, and in its absence.

Julian Dibbell wrote a memoir of his time in LambdaMOO, My Tiny Life. He describes an attempt to get an overview of the essence of the LambdaMOO environment – a bird’s-eye view, a map. He used a hot-air balloon. But it was a virtual, entirely text-based hot-air balloon. Its output was snippets of descriptions of random locations, as if he was drifting over each one in turn. It could probably have spat out an ASCII map or something, but that wouldn’t exactly have given him the essence of what he was looking for. (If this sounds daft, remember this was a journalist in an experimental environment twenty-five years ago.)

So he’s pottering around the notional sky in his virtual balloon, and it hits him: the map really is the territory. The best map of an invented place is the place itself, because every distance is there by design. You can only read that map by travelling the distance. And reading it is like reading a novel. You can’t expect the experience to remain the same the second time, whether fast-travel is enabled or not.

Pavel Curtis left PARC Xerox to found a company that built conferencing software. Microsoft acquired that company, and the software became Microsoft Office Live Meeting which became Microsoft Lync which became Skype for Business. That’s what LambdaMOO spawned, and that’s how the dream lives on. You can find that depressing, if you like. But I’d like to believe that under every Skype for Business conversation, there’s a sewer full of goblins.

I always find the most compelling part of an MMO to be that initial period of on-foot exploration, when the world seems impossibly vast, and your eyes follow with envy a player passing you at speed on a mount. Fast travel in some form or another seems like it needs to find its way into everything, in the end. The demands on free time, and perhaps our own impatience makes it so. Still, while I do lament the ‘shrinking’ of the world that comes with it, I do always have those fond memories of striking out into the unknown, on an hours-long journey filled with peril and discovery. Occasionally I’ve tried a reboot, an attempt to recapture that feeling, but when you already know what’s out there it’s hard to retread those steps.

I think I could resist a Sunless Sea fast travel mod. A huge part of the appeal of that game for me is the feeling of setting out on an adventure, seeing Fallen London shrink away in my mind’s eye (and occasionally crawling back into port on barely more than fumes). Less about the geography and more about just what’s going to happen to me along the way.

I feel in a similar way every time I replay the old Final Fantasy games. In the beginning I have to trave through the desert, or the forest, and every travel is an adventure. When I finally get the airship, I have a magnificent feeling of unbridled freedom, but it’s like a tiny bit of challenge is lost.

Thanks for writing this!

Well, thanks for making the thing that let me write it! You opened an awful lot of doors.

I’ve been contemplating informational distance for a while now. I actually use your term, nyctodromy, because your Parabola and Mansus were huge inspiration towards the idea. A Not-space, where distance isn’t very real, but the knowledge of how to get where you need to still creates a huge and mysterious world to explore.

There are obviously real world occult maps, which can include The Divine Comedy, but there are also a precise substitute for those – mathematical maps, like the map of the Mandelbrot Set. It’s a shape, a fractal, infinitely(literally) complex thing that doesn’t actually exist in anything physical, but is constantly explored, with new places and sights discovered.

There’s the Chronicles of Amber novels, where main characters have an ability to teleport to any choosen place across infinite number of parallel worlds. There is distance, but the distance is in not being seen, not being predictable.

There are Minecraft servers where everything great that players will build will be destroyed by others – unless one can hide it. Minecraft’s world is much larger than the surface of Earth, so probably nobody will ever stumble at random in your hinding place of choice, but you want to show off your work to others, right? Do you trust them? There is distance, but the distance is in not being seen, not being predictable.

There is the House of Many Ways book (named amusingly similar to House of Many Doors, an attempt at Sunless Sea), that takes place in a seemingly infinite house where one moves around by executing on a set of instructions. To get to the bathroom you knock on the door three times, open it with left hand and turn to the right when it opens. Change any part of the instruction an you’ll end up in some unexplored hallway. Probably there’s nothing there. Probably.

There’s generally the hypertext things. There’s no movement, only instructions. Change a letter, move a bracket, and you’re in an unfamiliar place. Probably there’s nothing there. Probably.

There’s the magnificent Antichamber, the game with best fast travel mechanic I’ve seen. You start from the map, having a single location on it. At any point you can hit one button to return to the map, and from there to any place you’ve discovered. The thing is – Antichamber is a puzzle game. An “open world”, nonlinear puzzle game. It is set in a none-euclidean maze that reacts to your every step. If you get to a new location, that means you’ve learned a lesson. There’s no reason to repeat the travel, there won’t be the same revelation again, because it’s already nested into your understanding of the game. My first playthrough took 12 hours. My second, from the balnk save file, from that single map location, took 14 minutes. Because I knew the lessons now, and the Antichamber doesn’t demand kilometers of walking or kiting a troll. If you know the way, you will pass.

There’s no conclusion yet, but, in part thanks to your work, a labyrinth of directions and adresses took root somewhere beneath my skull, and one day – one day – it will finally bear fruit. Thank you.

“House of Many Doors” is not an attempt at Sunless Sea — in many respects I’d say it’s better!

Not to disrepect AK and co, of course — just my opinion.

This was a great bit of nostalgia. I never used this, but do remember reading about it. Some interesting comments here as well.