Lore of Babylon

I wrote the article below for Wireframe, a British game dev magazine which ‘lifts the lid on video games’. And, inexplicably, lets me have a monthly column.

Stories are my jam. I make narrative games, I co-host a narrative podcast, and I studied English lit at university before I got a proper job. But I have different feelings for lore, the pickles in my narrative hamburger. A few lend some much-needed piquancy to an otherwise undersexed sandwich. Too many is like flushing your tongue down a vinegar loo. So I’ve developed a simple guide to establishing the lore content of narrative games: they’re Hobbits, LOTRs or Silmarillions.

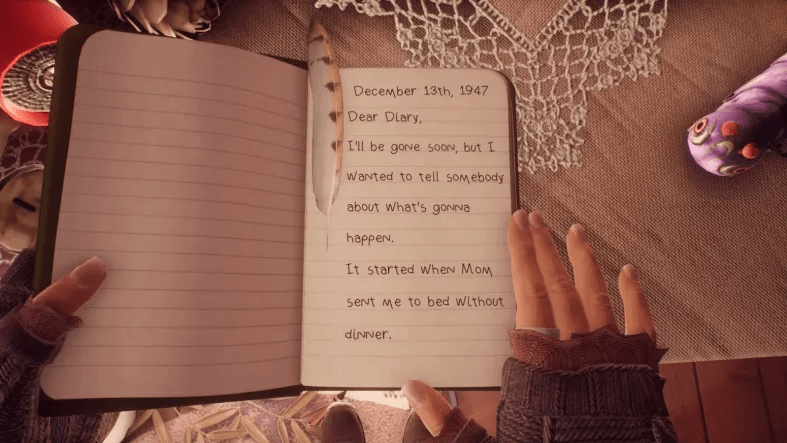

The Hobbit is an approachable, plot-driven story with mass appeal. It entertains childrens and adults and relies on simple mythic touchstones: a quest for treasure, a slumbering dragon, a great evil bad guy. You don’t need lore to read The Hobbit. If you have insider knowledge of the Silmarils and the origins of wizards and the Ring, that’s great. But you can just as easily appreciate out-tricksing trolls and escaping wood elves in wine barrels without it. The game equivalent is Gone Home or What Remains of Edith Finch: well-made, much beloved and entirely self-sufficient.

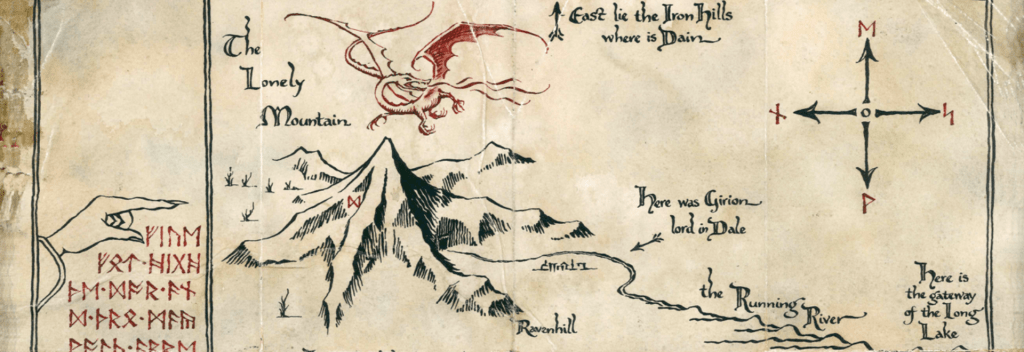

The next level up is The Lord of the Rings. It’s bigger than The Hobbit and has more words with Capital Letters. It’s no longer ‘dwarves live underground’ – now it’s ‘Aragon son of Arathorn is the true heir to Isildor’s throne, and that’s why he can heal people with his hands (sometimes)’. The narrative spends time explaining the world and how it came to be. Characters’ motivations are linked to history and world events. There’s extra lore available but it doesn’t get in the way of the story – it’s tucked away in footnotes and appendices.

LOTRs are Diablo and Assassin’s Creed. You can read a bunch of extra stuff in collectable codices and some bits make more sense if you’ve played the earlier games, but broadly speaking, it’s more about the moment-to-moment experience. Did you know that Azmodan, Lord of Sin, originated from one of the seven heads of the great dragon Tathamet? For most Diablo fans, he’s just that spider-lookin’ tubster you fight at the end of Act III.

But some people do care about the great dragon Tathamet. For them, there’s The Silmarillion.

How do you know if someone’s read The Silmarillion? Don’t worry, they’ll tell you. Silmarillions are the hard-core games, the Dark Souls of narrative, the ones whose openings take two hours and are called ‘Prologues’ and give you a headache because they try to funnel ten years of narrative design through a grommet the writer’s bored into your skull. They’re your Tyrannies and your Tides of Numenera, who boast of word-count and whose forums are full of nerds arguing over which war nine epochs ago most influenced the UI. The lore is front and centre. The introductory FMV is a Dadaesque display of proper nouns and references you don’t understand and at some point there’s definitely something on fire. You’re here because the Throng of Boo were destroyed by the treachery of Ka’al the Deceiver as he rose to power in the Third Age of Meep. (If tooltips aren’t working in your edition of this blog, please email Alexis to complain.)

Ironically, there is no ring to rule them all with narrative approaches. Some people bloody love a wiki’s worth of worldbuilding. Others are driven to drink. But whatever your preference, it’s helpful to know what you’re getting into – no one likes surprise pickles.