What can change the nature of a game?

Let us assume, against all evidence to the contrary, that Weather Factory has frightening corporate lawyers. Let us assume, for the sake of stereotyping, that their names are Victoria, possibly Rafe, or, if we’re really pushing the boat out, Gerald. These lawyers have told me to start this post with the sentence ‘YOU CANNOT YET BUY TRAVELLING AT NIGHT’. It is in its first ever Steam event – the isometric RPG sale – but only as a wishlistable ‘coming soon’ entry. But this is an exciting moment, and I thought it was a good excuse to talk about some of the isometric CRPGs that have gone into Travelling‘s design and what specifically we’re iterating on. Starting with the one everyone knows:

Disco Elysium — COMBAT-FREE, SKILL CHECK MODIFIERS

Disco was the first CRPG that said ‘if the text is good enough, you don’t need combat’. I believe the devs originally planned to include combat and then cut it for budget reasons. If Disco hadn’t (perhaps accidentally) made this genius leap – and if the game hadn’t been incredibly successful, no-combat and all – we probably wouldn’t be making Travelling today. It’s already basically stupid that two people are trying to develop an entire CRPG on their own, but we would be looking at a 5yr+ dev cycle if we had to design and implement an entire combat system on top of everything else that’s already going into our game. It would also probably not be very good, because we’ve never designed a fully-fledged combat system before, and the bar is set high by great combat in other RPGs. So thank you, DE, for being our story-heavy vanguard. You set players’ expectations so devs like us can come out and say ‘we’re making a CRPG but there’s no fighting!’ and people don’t boo us off stage.

Travelling uses one other thing that really specifically draws from Disco: its underrated meta modifiers. Wait! It’s much more interesting and significant than it sounds. Let me explain. Everyone understands that RPG characters use, improve on and specialise in skills. CRPGs that grew from tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons also have an established norm that you roll dice and compare the number to a character’s skill level, determining whether that action succeeds or not. Disco uses this system (without being as literal about it as, say, Baldur’s Gate 3), but also goes further. Modifiers are not just difficulty checks against skill level, but incorporate prior actions (a -1 modifier for two pétanque players if you throw away their ball) and relationships (‘+1 The lieutenant trusts you’). My favourite modifiers even take into account what you have in your pocketses. For example (mild spoilers below!), at one point in your murder investigation there’s a Hand/Eye Coordination skill check to determine what type of weapon shot a particular bullet. Stacking on top of your character’s base Hand/Eye Coordination skill level, potential modifiers include the following:

| • +1 Aware of the name of the antique rifle you found. |

| • +1 Encyclopedia said this came from a breechleader. |

| • +4 Have a similar rifle on hand. |

If you’ve found the ‘similar rifle’ in question elsewhere in the game and didn’t sell, store or lose it, the fact that you have a gun you can physically compare to the bullet you’ve found give you a natural and rewarding boost to your chance of success. It’s a small thing, but the game ‘knowing’ what you have in your inventory feels like it steps over a hidden barrier somewhere between game and real-life. Rather than relying solely on numbers and dice rolls, Disco responds like a human and says ‘ah, you’re thinking that if you were a real human trying to identify a bullet, you might compare it to that gun you have and see if it fits. Well, be my guest’. This felt magical when it happened in-game. Travelling, we hope, will also take the opportunity to be human, when it can.

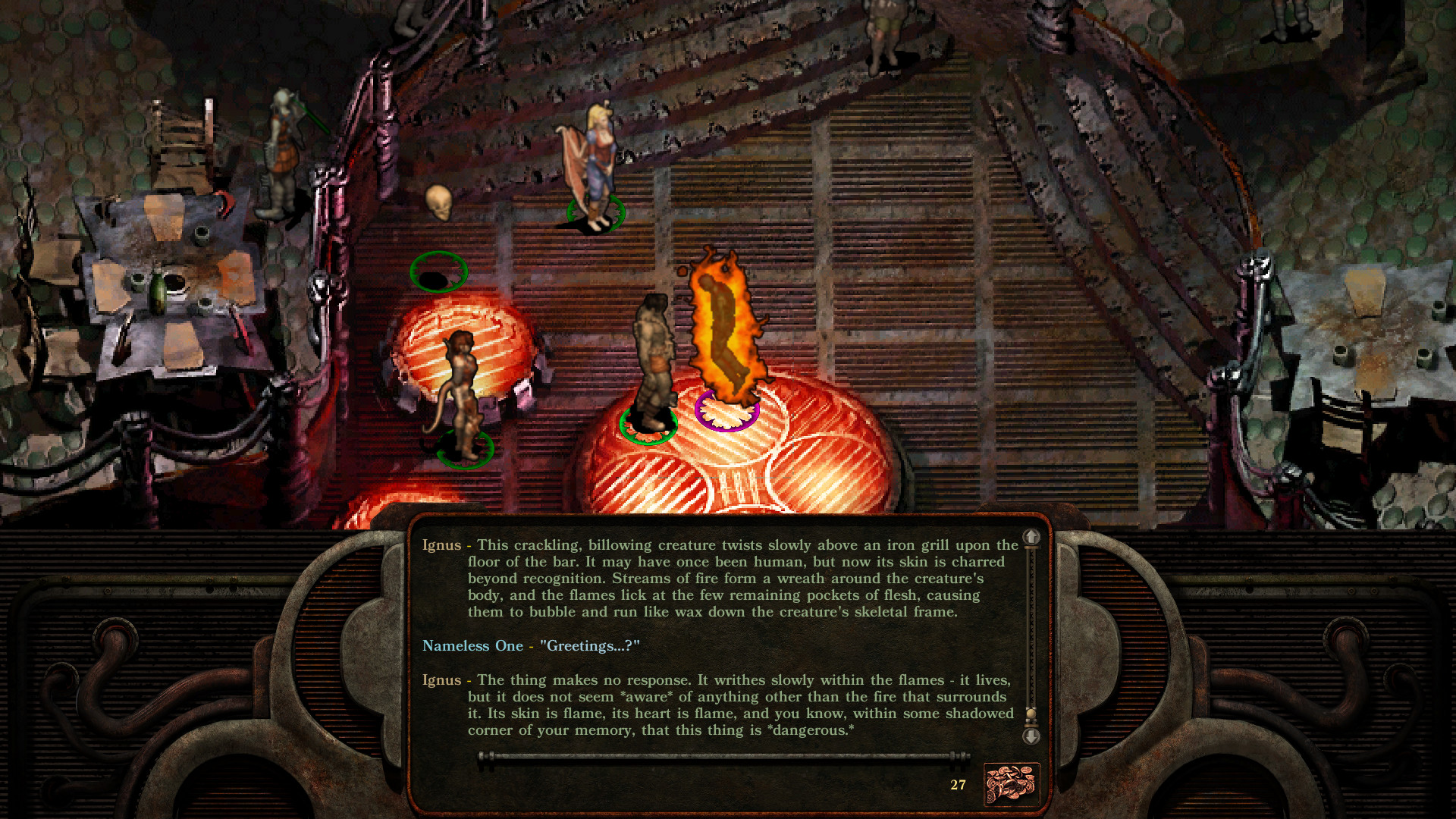

Planescape: Torment — IT’S WEIRD

Junk opens portals to other dimensions. Your best friend is a lascivious floating disembodied skull who can learn new battle-taunts by watching you get murdered by a reanimated petrified warlock. You meet a wall which happens to be pregnant and a giant war-golem whose origin story is ‘MINOR EXPRESSIONS OF PAIN’. I played Torment on easy mode, bypassing most of the combat requirements. I’ve heard from CRPG communities that this is often how people recommend you play Torment, beloved twenty-six years later for its story and writing but not necessarily for its combat systems. If you’ve played any of AK’s work previously (Fallen London, set in a funny gothic post-lapsarian city stolen by bats; Sunless Sea, a mix of Coleridge and cannibalism; Cultist Simulator, where you peel back the skin of the world; etc), you’ll know he does pretty good weird too. Travelling is shaping up nicely in that department: we’ve already mentioned sticky widows, ‘puppy mike’, and teased an image of vast, floating jellyfish-like fronds of something over France. This is before we get into any of the Incorporates or Ministries’ larger purpose, what’s going on with a trio of mysterious red nuns, why cities are encased in amber or why the first piece of art we ever shared has a giant beetle-like thing in the background.

I’ve also drawn a lesson on simplicity from Torment. This game launched in 1999. It was explicitly based on D&D’s world and systems, and as such, some of them come across as a bit… arcane to modern audiences. For example, Torment taught me the meaning of ‘THACO +2’. I say ‘taught’, but… it didn’t do anything of the sort. It said ‘THACO +2’ and I said ‘hey AK is that good’ and he said ‘oh wow THACO I haven’t heard that in a while’ and started explaining and thirty minutes later I screamed. Torment also ‘taught’ me that you have to learn spells and then memorise them and then only use them once before having a nap because that’s fun, and that Detect Traps is a skill designed by someone who hates you.

I’m hamming this up a bit – Torment is magical and I love it – but it’s been a good reminder for us to keep usability in mind, even when developing a sprawling, mad, often bizarre CRPG. One of the things we want Travelling to do is keep AK’s wonderful writing and worldbuilding but not hide them behind difficult game systems. Games like Cultist or Sunless Sea use game mechanics to pace player’s consumption of the games’ writing, and to make each storylet feel like a delicious text-based reward. Travelling aims to lavish AK’s writing around like Ebeneezer Scrooge on Christmas morning. We hope to do this without diminishing how much you enjoy actually reading those words, and of course while avoiding the dreaded ‘lawnmowing’ effect (where you feel like you have to click through every branch of conversation because you don’t want to miss anything, and reading starts feeling like a tedious chore). I think we’re on our way there, but the experience of playing D&D systems from the 90s (‘Second Edition!’, says AK, like a nerd) in a text-heavy game is a useful cautionary tale.

Shadowrun — HUBS, UI

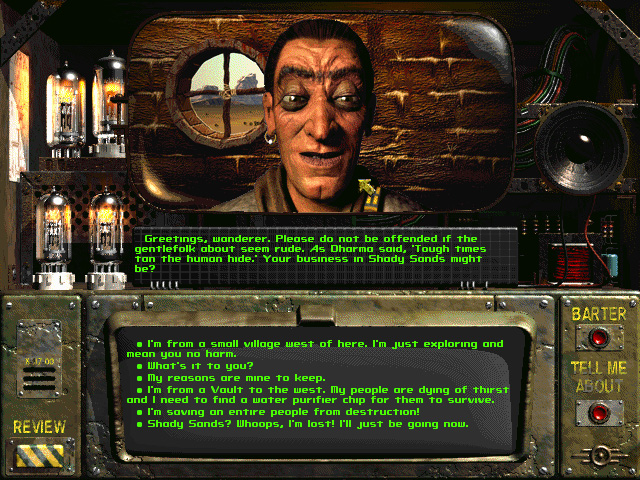

OK, full disclosure here: I haven’t played Shadowrun! This beloved, seemingly slightly niche series is the next one in my queue. But AK’s played all of them, and found they hooked him much more than he expected them to. The series was the first one to innovate from traditional centred dialogue text –

Fallout 1 (1997)

– to the right-hand sided, vertical UI that so many modern narrative-first CRPGs now use.

It might seem like just a cosmetic change, but it really makes the act of reading enjoyable and gives lots of text room to breathe. Many people think Disco did it first – I think they most likely came to the idea independently, as Kurvitz said their dialogue bar was ‘modelled after the experience of reading Twitter on a phone’ – but Shadowrun did it as early as Returns in 2013, which is the first instance I’m aware of. Readers, tell me if you know of a precursor.

A subtler takeway from Shadowrun is the relationship you build up with your home hub. This is particularly apparent in Dragonfall and Hong Kong. You return to them over and over again over the course of the game, meaning you not only build an emotional connection with the place but also begin to feel actually safe when you’re there. The location becomes associated with the relaxing feeling of not being on a stressful mission somewhere else. We hope to develop a similar situation with Travelling‘s Rosa Mundi circus. There’s not a huge amount of comfort to go around in 1940s Europe, but your itinerant home full of cheerful flags, welcoming lighting and people who are happy to see you should act as an emotional counterweight to some of the frightening, hostile things you might encounter elsewhere. But: more on that later down the line!

For now, a toast to all the CRPGs that came before. We love you, you all seem weirdly evergreen, and I can’t wait to launch one that might – if we try very hard and are very lucky – end up in the same part of people’s minds as all the greats that came before. To art! 🥂

Quotes from games I love, they all stood out as though highlighted and I grinned from ear to ear. I may have to replay Torment now.

The safety of a Hub is definitely present in Mass Effect series: the Normandy becomes a place of socialization and respite between frenetic missions.