“Too long near the woods to be frit by owls”

Last year, Lottie and I spent a pleasant week with her parents in a place called the Hidden Chapel (this is true) in a village called Zeal Monachorum, or cell of the monks (this is also true). This blog post is about neither of those things, but it does concern an antecedent to the Prayer Book Rebellion.

What, you might ask if you’re not from Devon, is the Prayer Book Rebellion? What, you might ask if you’re not from the UK, is a Devon?

Ireland on the left, Britain on the right.

My old geography teacher liked to point out that Britain looks a lot like a bloke carrying a pig under one arm.

The man’s head is Scotland, the bloke’s head is Wales. The rest of the island is England. The foot coyly pointing southwest is the part of England comprising the counties of Devon and Cornwall – a long long long time ago, the Kingdom of Dumnonia. London, where I now type this, is the orrible grey blot in what Lottie won’t let me call ‘Britain’s bumcrack’.

The key geopolitical details here: what are the remotest parts of mainland Britain from London? The answers: the man’s head, the pig’s head and the man’s foot. (NB ‘remotest’ not ‘most distant’. There’s a lot of Northern England, but it’s not at the end of the line.) As you might expect, then, the parts of Britain with regional languages and significance independence movements have been Scotland, Wales and Cornwall.

Most English-speakers have heard of the Scottish nationalist movement, if only because of Mel Gibson. The Welsh nationalist movement is less well known, though my generation of Brits might recognise the name Meibion Glyndŵr, the sons of Glyndŵr, the organisation that fire-bombed English holiday homes in the 80s. The Cornish nationalist movement is, I think, largely unknown even to most Brits, though there’s still a registered political party, Mebyon Kernow, the Sons of Cornwall, campaigning for greater Cornish autonomy. But back in the day, you can bet they noticed.

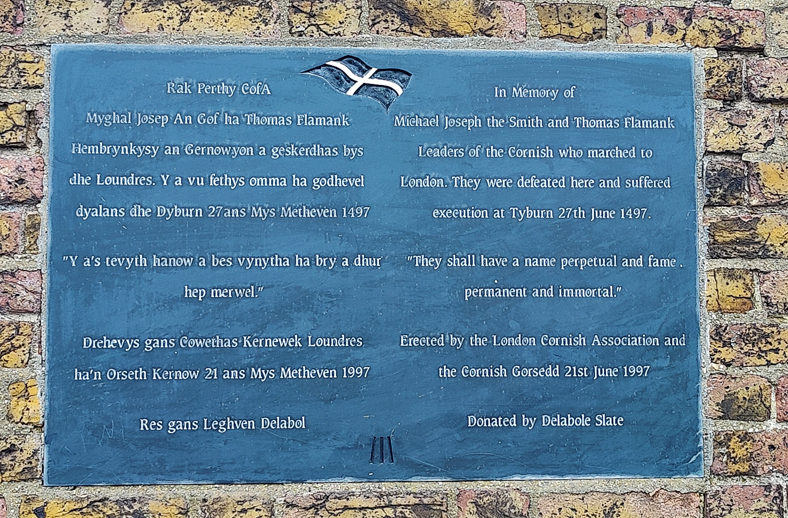

Between 1497 and 1549 there were at least three major uprisings in Devon and Cornwall – in fact two of them were in 1497. The third one, the Prayer Book Rebellion, is the best known and most picturesquely named. But in the first Cornish rebellion of 1497, the rebels made it all the way up to London – round the corner, in fact, from me and Lottie. Here’s a plaque at the north entrance to Greenwich Park commemorating their defeat.

I’d cycled past it literally hundreds of times before I started reading up on this stuff, vaguely assuming it was a war memorial (London is stiff with war memorials). And it is, but for one of the odder skirmishes of this island’s bloody history.

Back to the Prayer Book Rebellion fifty years later. One of the reasons the Cornish, like the Welsh and the Scots, kept rising is language. The Rebellion kicked off when London tried to enforce church services in English. Like most rebellions, it wasn’t just about the language (‘Kill all the gentlemen!’ was one of their rallying cries). But a distinct language is often the crucible inside which a rebellious identity can achieve boiling point.

You’ll have noticed above that Meibion Glyndŵr (the former Welsh nationalist organisation with occasional terrorist tendencies) and Mebyon Kernow (the current Cornish nationalist organisation with, I should be clear, absolutely no terrorist inclinations) are similar sorts of names. You’ll have noticed also that Wales and Cornwall are just across a short stretch of sea from each other. Welsh and Cornish are both Brythonic Celtic languages – both remnants of the tongue spoken in this island before the Saxons spread across the country from the east. (Nowhere’s not been invaded, even countries that are generally better known for invading other countries.)

That word ‘Brythonic’ shares a root, of course, with ‘Britain’, but also with ‘Brittany’, the region in Northern France that was once called Britannia Minor, Lesser Britain. (That’s why Britain was, in the twelfth century, first referred to as Great Britain: not out of imperial enthusiasm – it hadn’t got around to invading all those places back then! – but because it was Britannia Maior, the bigger Brythonic region.) The Welsh, Cornish and Breton languages are all as close as birds on a roof-ridge. And this brings us to Book of Hours, and to its location the library of Hush House, on Brancrug Isle by Brancrug Village.

‘Brancrug’ is a cooked-up Brythonic etymology. I wanted something that could pass as a Welsh or a Breton or a Cornish place-name without nailing it down to one place. (That might not quite work for a native speaker of one of those languages… although alas there are no native speakers of Cornish, not any more.) It should mean something like ‘Barrow of the Raven’ or perhaps ‘Crowsgrave’.

And it should recall one of the nearly-submerged features of this part of the world: we’re an isle of odd corners and relics. The Beatles and the Empire and Shakespeare, sure, but Wales and Cornwall and Brittany are Brecheliant Forest, Dinas Ffaraon, Britain before the Saxons; the Britain of Arthur before Malory dressed him up like the knights of the War of the Roses; of people who perhaps had to watch for the shadows of giants. The places where all that happened don’t exist any more, but that doesn’t mean you can’t visit them.

We have been inspecific about exactly where Hush House is. We might have to nail it down further, or we might have to determine that it’s in the Bounds, accessible from Ynys Prydain when the mists rise. But if I were a fifteenth century Cornishman hiding in a hedgerow as the King’s horses trampled the ground and spoilt the frost around me, then no matter what I’d done, Hush House would be the place to go.

So THAT’S why Great Britain is called “Great” — I always assumed it was simply because the island is big. As someone with Cornish ancestry and surname, this post was a particularly interesting read. I’m really looking forward to Book of Hours, too, especially as I just finished Against Worldbuilding.

Really wish for the Bounds location, just to get more Mansus landscape. We had barely any detailed description of House-of-the-Sun pastoral, and it sounds like something that would live rent-free in every adept’s mind, and if there’s anyone who definitely can write that it’s you. Like, I re-read the Malleary dream at least bi-weekly and often laugh and weep doing so, but when I tried to run a more adept-heavy Secret Histories tabletop, I found myself unable to really describe the more simple parts of Mansus in some actionable way, and that made me very sad.