Making: The Sibyl’s Leaves

I’ve talked a lot about the Tarot of the Hours, and I’ll talk more in future about our upcoming stained glass tarot deck. But I haven’t done a deep-dive into our Sibyl’s Leaves, a traditional 52-card playing card deck with a ‘zingara’ cartomancy twist. Here goes!

Step one: why am I even making this?

Our merch has to meet two criteria before I go ahead with it.

★ It has to be something people might want, regardless of whether they’ve played / heard of / like Cultist Simulator (so no ‘Lore of Cultist Simulator‘ books).

★ It has to be something flavourful and interesting that fits our boutique-y, occult-y vibe (so no ‘here is a mug with our logo on it’, either).

There are a few other practical criteria I take into account too, like ‘is this very space-intensive, and if so, where will I store it in my flat without Alexis getting cross with me’ or ‘is it even legal to send boxes of chocolates to the EU? How long does it take before chocolate goes off, anyway?’

I liked the idea of a playing card deck because

★ people like cards, and the Tarot of the Hours is our best-seller;

★ sales of playing cards surged in lockdown, as people turned to inside and/or wholesome entertainments;

★ I could make a dual-deck that served traditional card fans as well as spooky divination types.

Step two: what’s ‘zingara’?

The word is a corruption of 18th-century terminology from Italy (‘zingari’), Germany (‘Zigeuner’) and India (‘zingani’), all referring to ‘gypsies’. Telling your fortune with playing cards started with them, though cards have a very potted and complicated history going back to the very first gambling games centuries ago.

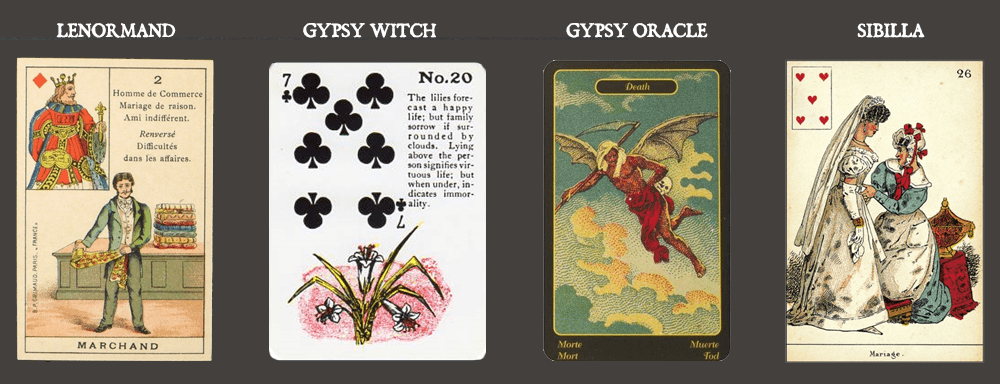

There are several variants of these zingara cartomancy decks, called things like ‘gypsy oracle’, ‘old witch’ or ‘sibilla’ cards, and they all bleed into each other. A fourth popular version, the Petit Lenormand, is named after the most famous cartomancer of all time, the 18th-century Frenchwoman Marie Anne Lenormand. She derived her own variant of older oracle cards and became wildly popular during Napoleon’s reign (before dying and leaving her nephew half a million francs, at which point he, like any good Catholic, burned all her stuff).

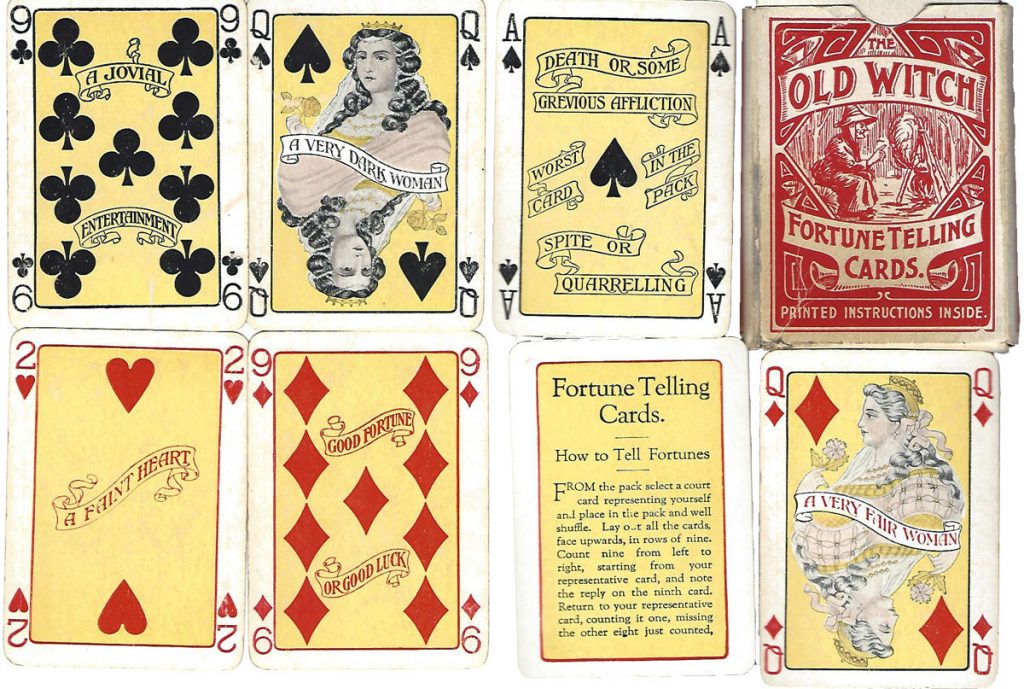

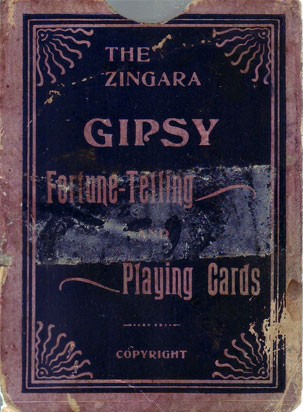

The only actual zingara deck I managed to find was this one, from the 1910s, and even this has the word ‘GIPSY’ on it.

The key thing to take away is that there are a variety of distinct fortune-teller-y rule sets being munged together and teased apart and called something different and played about with, over countries and centuries. It’s fascinating and we don’t know much definitive stuff about it. This is very fertile ground.

I knew I wanted to use the traditional 52-card deck, the usual four suits, written fortunes on all cards and Cultist Simulator imagery. So despite the difficulty in finding examples of the zingara deck in real life, I had a clear idea of what I wanted my version to be.

Step three: getting ready to make the thing

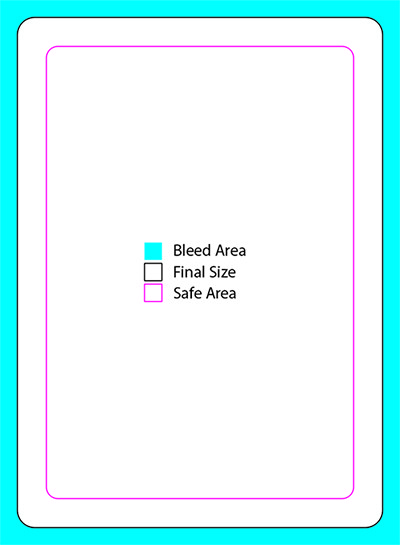

I did all the tedious work of finding a good local printer when I was working on the Tarot of the Hours, so the design process starts further along than if you’re starting your merch from scratch. But tarot are usually printed larger than traditional ‘poker’ playing cards, so I asked my printer for their poker card template. This gave me a blank canvas marked with safety, bleed and cut lines.

For the uninitiated, these define:

★ the area you can trust to show high-quality text and image detail without accidental cropping (safe area);

★ the area you need to extend your design to, if you’d like it to run to the absolute edge of the card (bleed area);

★ the area which will be shown on the card after it’s been cut to shape in production (the cut line or final size).

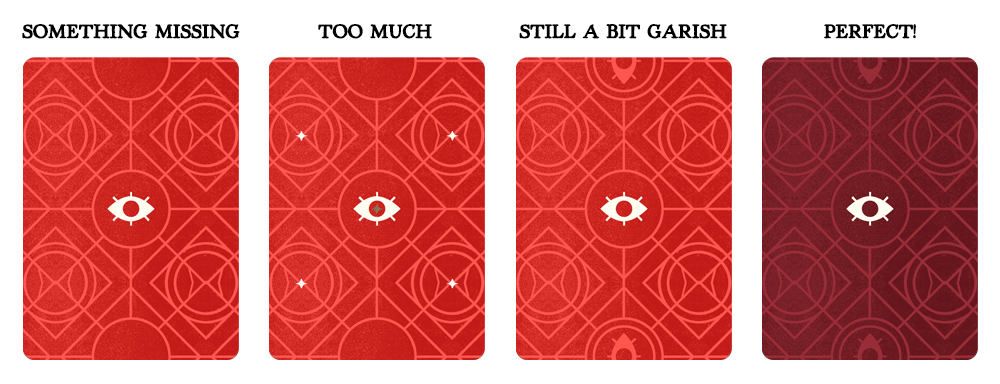

Basically, you don’t want to have immensely detailed text-orientated patterning around the edge, because this requires absolute precision in the printing process. There are machines out there which have this precision, but almost no general printer can promise millimetre accuracy. So be smart and hedge your bets with a centred, middle-friendly design!

Step four: actually making the thing

I started the designs with some very helpful restrictions. I knew I wanted Hearts, Diamonds, Clubs and Spades. I knew I wanted Cultist Simulator imagery. And I knew I needed to create space for reasonably-sized, reasonably-short text on the front of every card. Restrictions might not sound good for art, but they take you further away from the terror of the blank page. I love ’em.

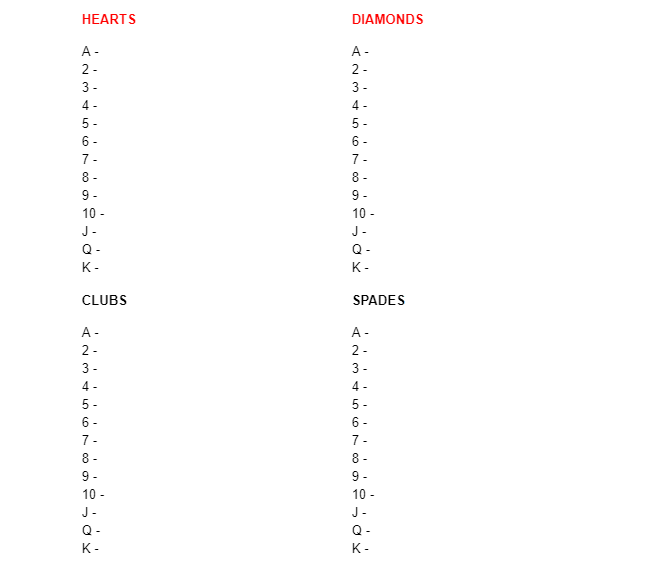

I started with a blank table that looks like this:

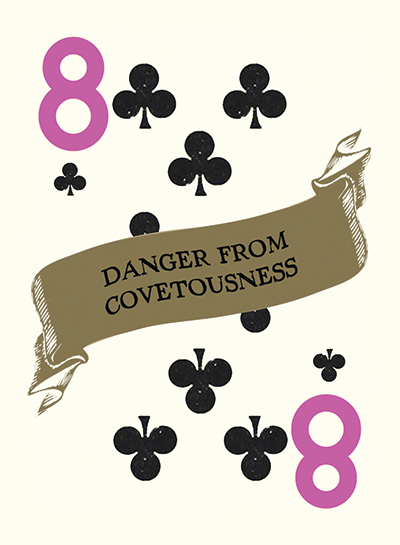

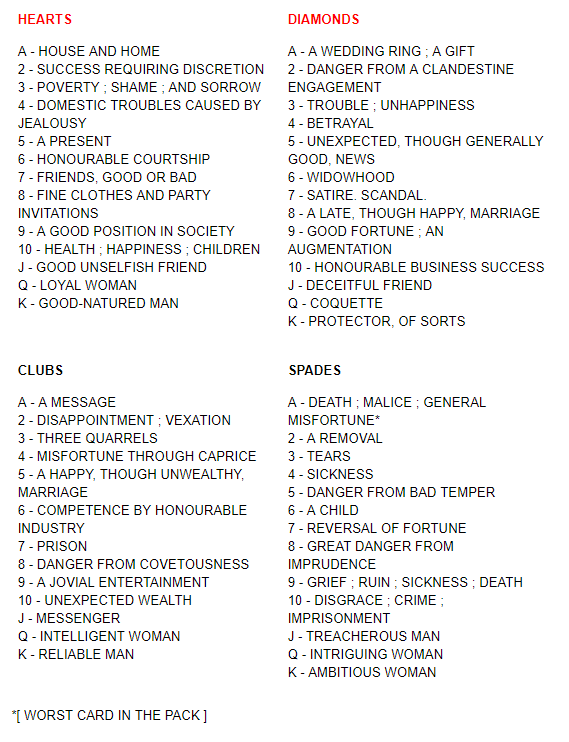

I then read around the zingara system, which as you can imagine, is about as varied as the people who used it. There is no one ‘right’ or ‘canonical’ system, so I munged together a bunch of things I read about in internet articles, reviews in 19th-century periodicals, or books like Edward Taylor’s History of Playing Cards. The zingara tradition I had chosen also dated back to the 1800s, so it originally included some outmoded and flat-out sexist and/or racist features. I didn’t want that in my deck, so I took the opportunity of updating some parts. Ultimately I ended up with this:

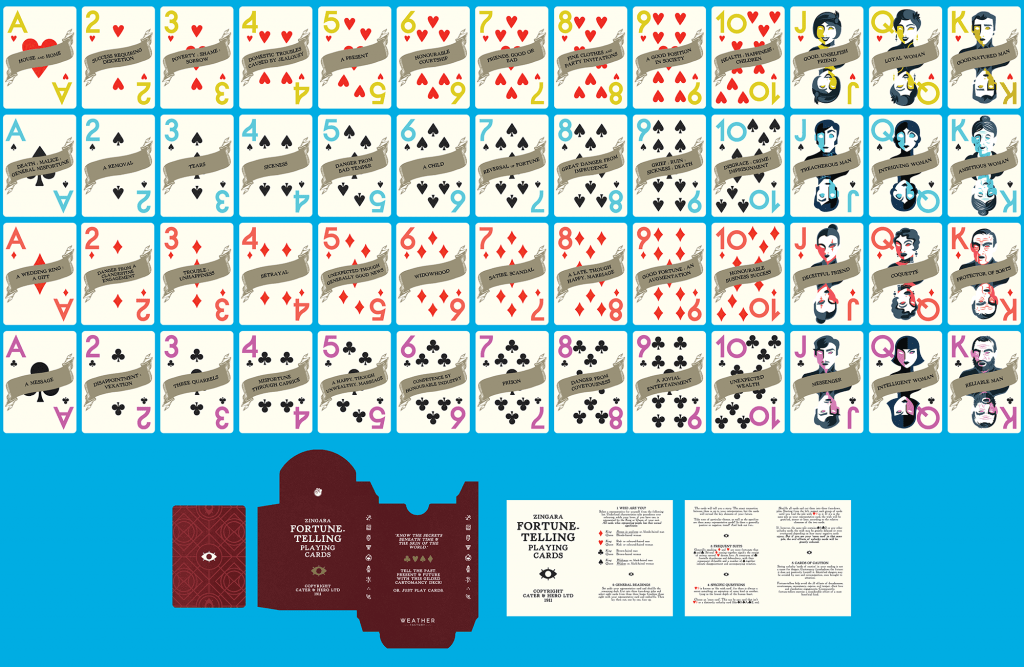

Now I had my four suits, and the meanings for each card. Time for some pictures!

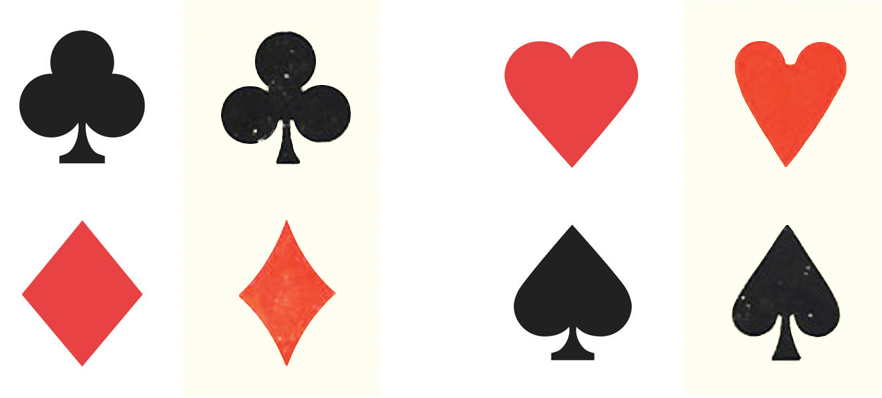

Modern card suits tend to use extremely crisp designs. I wanted my deck to feel old, so I mussed up the icons a little and chose a subtle cream colour for the background to imply old printers’ blocks and aged paper. Here’s a comparison of modern icons (on the left) versus my zingara ones.

The changes are subtle, but they really add up when you see them on the final designs:

Now for the face cards. These are the Jacks, Queens and Kings of each suit. This is where Cultist Simulator comes back in: bearing in mind the card meanings I’d decided from my zingara research, what Cultist characters best suited those descriptions, and also made thematic sense in groups? I also had to balance which colours worked best, bearing in mind Hearts and Diamonds are red while Clubs and Spades are black. Here’s what I ended up with:

I’m pretty happy with the results. Hearts, the friendliest zingara suit, has the jolliest colour scheme. Diamonds lets me lean into Cultist‘s Grail aspect by doubling down on the red. Clubs is a serious zingara suit, befitting cultists like Victor and Rose. And Spades, traditionally the worst suit of all, lets me put Neville in as a useless man. Win!

Step five: GUBBINS

Now the final part of the process. I had my main designs, but I needed a few more things before I could call the deck done.

I needed a design for the back of all 52 cards…

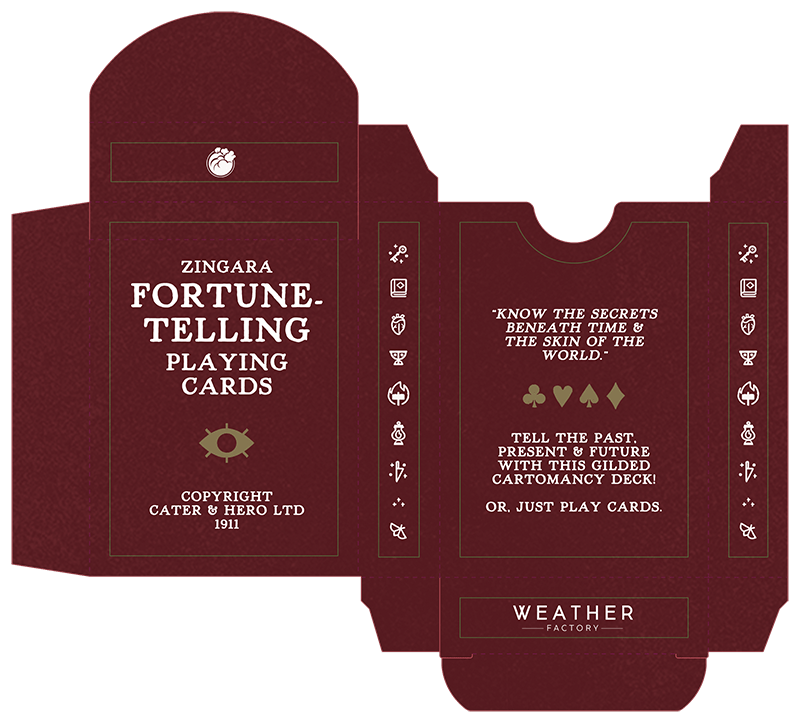

…a design for the tuck box containing the deck…

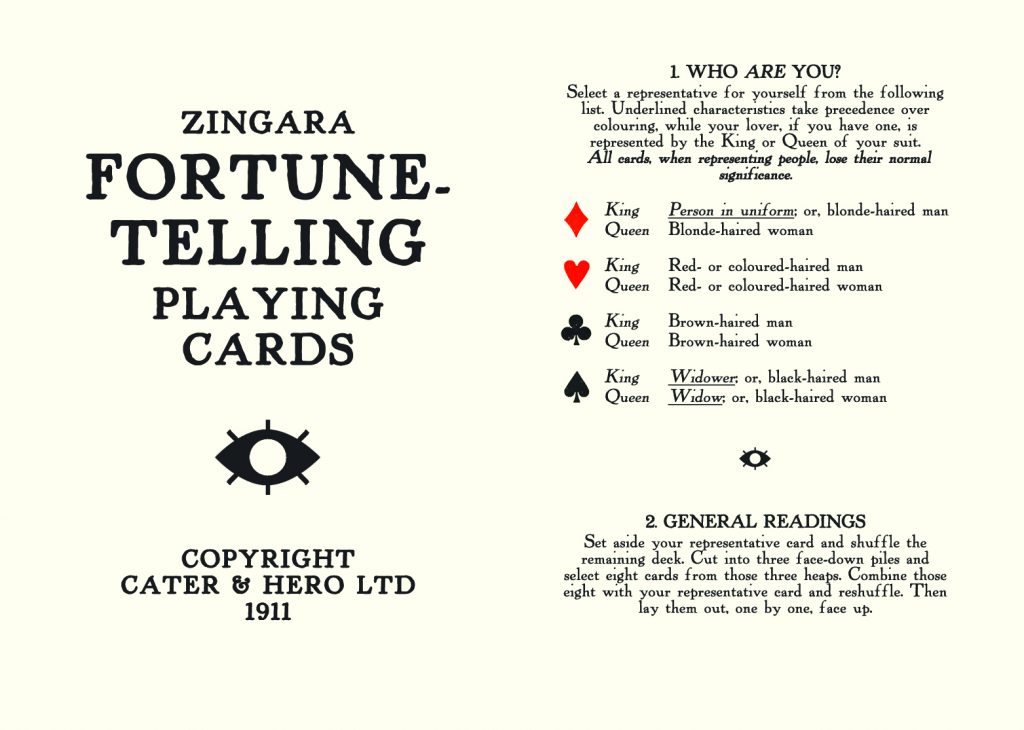

…to write up and design the instructions leaflet, explaining my version of the zingara fortune-telling system…

… and to sort gold foil accents on all cards and the box, to make it feel magical. The end result that I ended up sending to my printer looked like this.

Eagle-eyed readers might have clocked that I buggered up the instruction leaflet designs, because my mental object rotation skills are that of a dried sponge. So I was extremely grateful I opted to pay for one test deck before ordering 2,000 copies. PHEW.

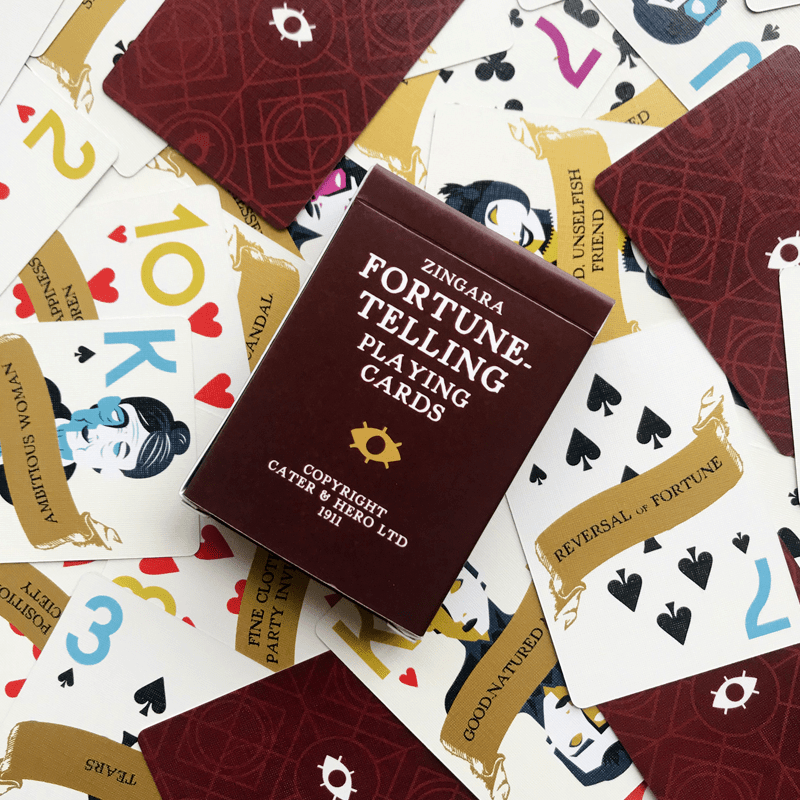

Step six: it’s done!

After the near-disaster with the backwards instructions leaflet, here’s how the deck came together IRL. I’m really pleased with them! You can get them here, if you like – but hopefully this has also helped explain how these things get made. Happy fortune-telling!

*Yes, this does mean my boxes live under the stairs. Into the cupboard they go.

I remember my mother telling me a story about a woman that she would go to as a teenager (probably in the early 70’s) to have her fortune read. The woman was blind and she read fortune with a normal pack of cards, like a Bicycle deck. Of course, my mother swore up and down about the accuracy of the readings, but I was always curious as to the method the woman used to read the fortune.

Your post illuminated a part of fortune telling I was previously unfamiliar with, so I just wanted to say thanks! The design for the deck is great, btw!